EXHIBITIONS

Latest Exhibition

Selau Pasege

George Funaki, Jasmine Tuiā, Jimmy Ma’ia’i

15th February–5th April

Join us for the opening event on Fri 14th February | 6–8pm

Summary

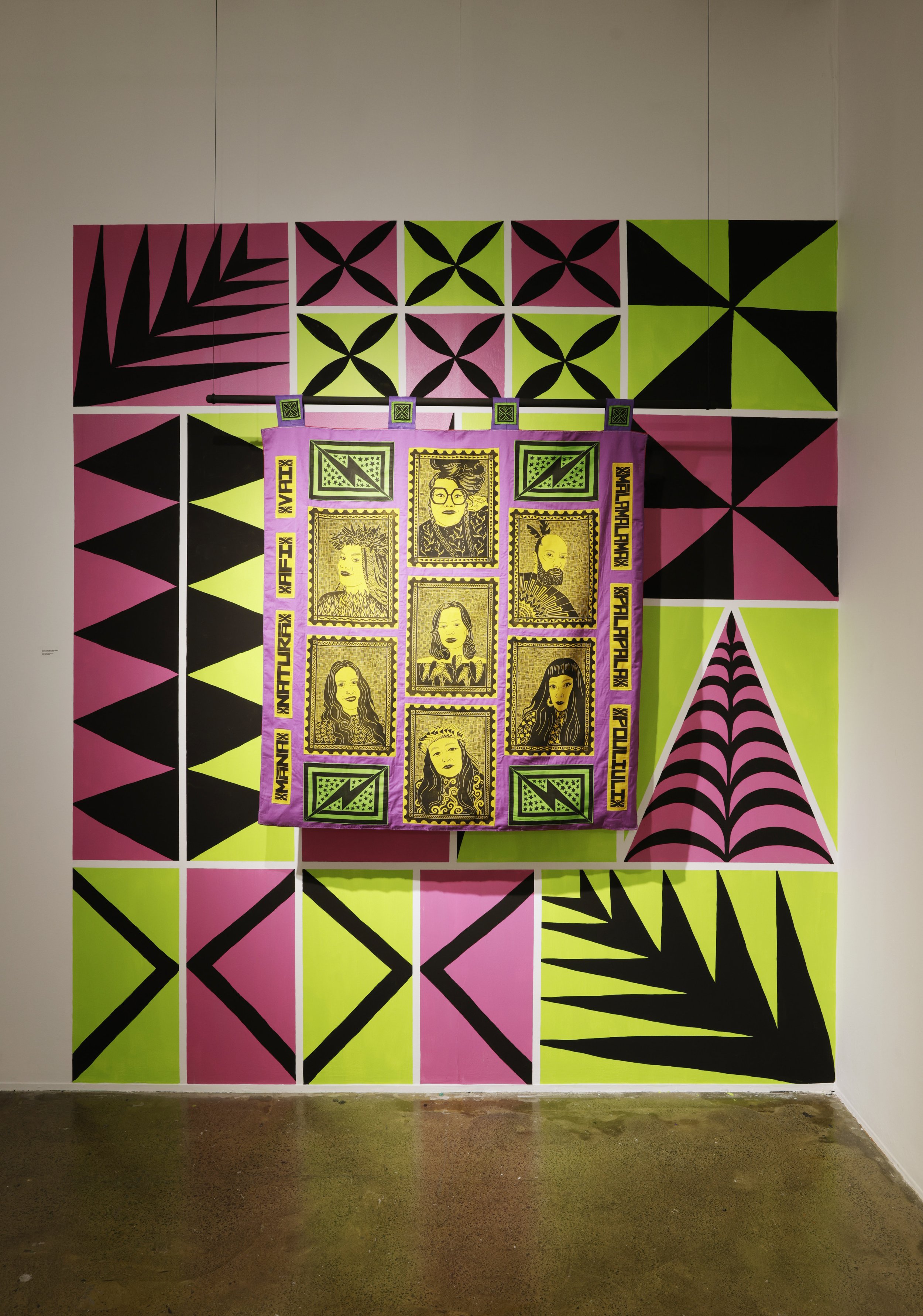

Curated by George Funaki, Selau Pasege offers an intimate glimpse into the richness of Pacific cultural treasures, or measina, and their enduring significance to Pacific communities. At the heart of this exhibition, artists Jasmine Tuiā and Jimmy Ma’ia’i, supported by Funaki’s moving image work, bring together their distinct artistic practices in collaboration, creating a dialogue that explores how Tāmaki Makaurau’s Pacific communities define their identities in a climate of underrepresentation and marginalisation. Selau Pasege celebrates the inherent culture that remains a constant for these communities as they adapt and excel despite these limitations.

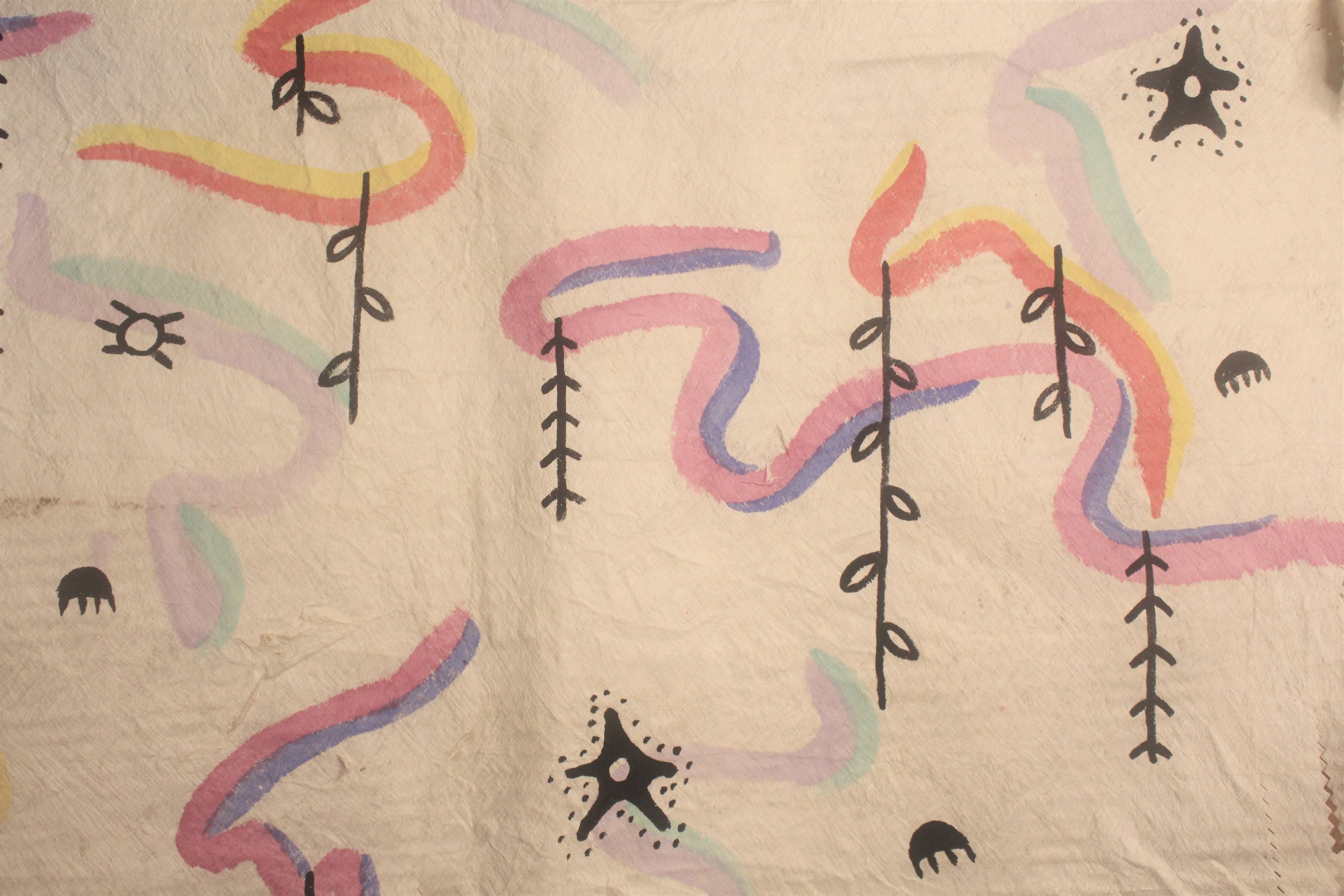

Measina encompasses both tangible and intangible heritage—from traditional objects such as tapa, tools, and artifacts to the values, practices, and knowledge passed down through generations. Tuiā, Ma’ia’i, and Funaki breathe contemporary life into these traditions, combining time-honoured Pacific techniques with modern influences to examine current perspectives and experiences.

Selau Pasege invites viewers to reflect on the profound ways heritage shapes us—both as individuals and as members of a collective community.

Artists

George Funaki an inter-disciplinary artist based in Tamaki Makaurau, initially established himself within the fashion industry as an independent designer and freelance project manager.

Concurrently, he has dedicated the past three years to refining his practice in creative direction, which has expanded into curation. His efforts aim to present a nuanced interpretation of the queer Pacific framework, specifically leiti, relevant to the experiences of New Zealand-born Pacific people.

Jasmine Tuiā, born in Apia Sāmoa is a tapa maker who uses embroidery to think about Sāmoan material culture and memory. From the villages of Matautu Lefaga, Falefa Anoama’a and Malifa Sāmoa, Jasmine explores her familial connections to these places through Sāmoan storytelling techniques and her siapo practice. Her work passions revolve around community arts access and facilitation.

Jimmy Ma’ia’i is an installation artist based in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland whose practice utilises found objects and materials, and the readymade. Of Sāmoan and Scottish descent, Ma’ia’i draws upon mixed-heritage experiences, cultural dislocation and the impact of colonisation in his artworks. Recent exhibitions include Spring Time is Heart-break: Contemporary Art in Aotearoa, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū (2023-24) and Ocean of Whispers, Enjoy Contemporary Art Space (2022-23).

Artist Talanoa | Jimmy Ma’ia’i and Jasmine Tuiā

Facilitated by George Funaki | 22 March

George: Malo lava, my name is George Funaki. I'm an aspiring curator. I'm five foot nine. I'm a Scorpio and just looking for someone to ooh, wrong show.

Anyway, hi. Welcome to Jasmine and Jimmy's artist talanoa today. I just wanted to celebrate with you guys and ask you all to give a round of applause for us all. So cool. Let's get started. Jasmine and Jimmy, can you introduce yourselves and what your practices are?

Jasmine: Thanks George, Malo lava le soifua, (Welcome everyone) my name is Jasmine Fotuotausala Tuiā, I come from the villages of Matautu Lefaga, Malifa Apia and Falefā. I also want to welcome those who are joining us online, today George, Jimmy and I will try our best to share some of the ideas and background behind this exhibition/project.

Jimmy: My Samoan isn’t as good as Jasmine’s so I will have to do mine in English, but I'm Samoan and Scottish. My Samoan family is from the villages of Sapapali’i and Fasito’outa and my Scottish family are from Edinburgh. I don't know how I'd define my practice. Maybe it's conceptual. I work a lot with sculpture, and things that fit my ideas.

George: So yeah. Cool. Just to go and get started in formalities or the formal questions, I hope you guys get to see the show after if you haven't already. It's gonna provide quite a bit of context. My question two: How do you start making? Do you begin with an idea, a story, or something else?

Jimmy: For me, I think I tend to sort of ruminate on an idea. Once that sort of six-month period is up, I think about how best to convey that idea. Generally, it's something close to me, something personal to me or something that I care deeply about. And then I go from there.

Jasmine: I guess it's different for me. I think the way that I started, making art was through uni and coming out of that, I did a lot of workshops and exhibitions. So the incentive would be to make for shows and workshops.

I had some time off making, so the incentive would just be going home and destressing. And, because my practice is on tapa su’i which is embroidery on tapa, I use it as a space to just chill out and not think about anything or just use it as something to generate my emotions and my feelings of the day.

But for this show, it was based on conversations. Jimmy and I work together, and we've done one show together [at Enjoy] in Wellington and just based on our friendships because we see a lot, we chat a lot, we yap a lot. So, all these ideas just generate from there.

So it's a good opportunity for Tautai and George to bring this show together for you to present those ideas in a tangible manner.

George: Question three. What materials or objects are necessary to your practice, and why?

Jasmine: Bark cloth and embroidery are important materials for me is. Another one worth talking about is the, I forget the word. What's the thing called? I'm looking at the cotton threads. Oh, I'm so sorry. I'm getting kind of blank!

The cotton threads! So embroidery is not traditional to Samoa. It's not traditional practice or process for decoration for tapa. So even though tapa is important as a material for my work, the embroidery is a marker of time, and the tools - without the tools there would be no tapa.

Jimmy: For me, I use readymade material or found objects. Material that I use quite regularly throughout my practice is this wood, the same wood that I've used, for the tools here. I find that the objects, and the material can also tell a story. In this case, it sort of tells a story about, the effects of colonisation, particularly New Zealand's administration of Samoa. The native word for this wood is ifieleele.

And they sort of okayed the deforestation of massive amounts of this native timber, for export. I use this material, often it's found or in some cases it's been decking timber, and sort of return it to like a traditional form. The tools that you see would've been made out of this timber or like a cava bowl. So, yeah, whatever material I use generally supports the narrative that I'm trying to sort of convey.

George: What does your making look like on an average day to day with you as practitioners?

Jasmine: Day to day? Barely. During winter, I'm like not doing anything at all. Because that's not when I harvest tapa. Most of my tapa are made in Samoa.

But as I was saying, the way that I use tapa, I just come home and I just stitch. I just come home, look at some tapa that I made already, and then I start stitching whatever that comes to mind. Sometimes it's text, sometimes it's flowers, like small ones. And then sometimes it's just me trying out a new pattern for embroidery.

Nothing's special, to be honest. It's just beating and scraping.

Jimmy: I don't know if I have a daily sort of practice.

It probably doesn't look like anything because it's just rumination. I think just overthinking these ideas. Yeah. That's what my daily practice looks like.

George: Moving up to our next segment, growing up and experiences in Auckland. Question five, how does growing up in Aotearoa influence your worldview and more importantly, influence your practice?

Jimmy: So I think, growing up in Auckland, specifically, West Auckland has played a big part of who I am today, but, also my practice, coming from a very much working class family - which isn't uncommon in West Auckland.

A lot of this work is sort of an homage to that, to them, my family included. But there's also conversations to be had about cultural dislocation, things like that. So growing up, away from your culture, you kind of have to, at least for me, I kind of had to figure it out for myself to some extent. I think it's really important as Auckland is, it's something like over 90% of our Pacific communities live in Auckland. I think it's important to acknowledge that, and I do so with my work. Also, we're sort of living within the effects of colonisation. Right?

So there's also that, that you sort of have to toil with.

Jasmine: Off what Jimmy was saying, it's a bit different for me. I grew up in Samoa, moved to West Auckland, went to Hamilton, came back. So I think, doing art has, well, coming from Samoa, I, my culture wasn't really something I had to question.

It was only when I came here, then I was like, oh, I'm brown and I have different values and cultures of understanding of the world. So coming into Auckland has really taught me a lot about diaspora. That was a buzzy thing to learn about in university. And then (I feel like I'm going to tangent) but the way that Auckland has influenced my practice is make me think about the nuances of identity especially as someone that's grown up in the culture and then coming and growing up in the same culture, but just in a different location. So talking about dislocation, it was a different role for me? I was away, but I knew who I am and what I was doing. But in terms of my tapa practice, the only thing that I felt like was hard or a challenge was accessing tapa materials because I it's important for me to go back and do it. Not traditionally, where it came from and, be with the community and people that does this every day.

Does that make sense?

George: Question six. Given your backgrounds, cultural backgrounds and separations from your homelands, do you see your work as a way to connect with your culture?

Jasmine: Do I see my work connecting with my culture? Yes. Big time. Big time.

I see it as, not so much connecting as staying within it. We had this other conversation the other day about how our material culture is parallel to other knowledge and materials the values that we have. But the biggest one being our language, and that's intricate and sophisticated. So, tapa for me is kind of that or the same language of trying to understand it.

It's very important. That's all I'm trying to say.

Jimmy: I think so – I grew up sort of told “you're a Samoan, you're a Samoan”. I never really doubted that. And it wasn't until I had started my degree at Unitec, and in my second year my grandfather passed away. And I sort of saw him as a link to my Samoan heritage. That's where I've been at for a little while now.

I want to know my culture - and I think my work kind of reflects that desire.

George: What challenges or adversities have you experienced as Pacific artists who have studied, worked, and exhibited in Aotearoa?

Jimmy: I think that’s a tricky one for me to answer because, you know, I can sort of operate to some extent, comfortably in both worlds, and there’s privilege in that, and I understand that you know, like, I've seen sort of my dad being a victim of racism and then the same person treats me completely differently. I don't know if I should really answer that.

Jasmine: I'm gonna speak about tapa making first, and the decorative style that I go with because embroidery is not common on tapa, I think that was my biggest insecurity of “am I supposed to be doing this? Am I supposed to be stitching on tapa? Is that appropriate?”

So that was the biggest challenge for my own practice. But I've overcome it because I know I can make the real thing. I've gone through the processes, and I've talked to the right people.

My great grandma and my grandparents, that's all that matters to me. And I always acknowledge that it doesn't represent Samoa. It doesn't represent my village. It represents me. It represents my family. It represents my own narrative and story with tapa. So that's a challenge that I dealt with early on. It's kind of like the authenticity thing - what makes a good tapa? What makes a real practitioner?

And knowing that art is not separate from us. And then in school institutions, oh, I think everyone's pretty familiar with how that is. For me as a Pacific woman that came through art school it’s a funny thing - it wasn't until I came here that I realised I was brown.

In university I didn’t have a lot of support and then also navigating it was putting up fronts just to go through university and institutions. I think it the biggest challenge for that is being able to just do it, just keep going and making things happen for myself, and I always think of my siblings or whoever's coming after us.

So the challenge with institutions is obviously racism. And I think the funniest thing about that is that in New Zealand, it’s under the radar, it’s not straight to your face. And I think if you just told me straight to my face, it'd be like, all good.

So that was a challenge in institutions. And then out of university, now that I'm working, it's trying to find a time to make. We work full time and, we talk about ideas all the time, and I feel like it gets I get stuck in my head a lot about thinking about art. Selau Pasege was a great way to be back to making.

Jimmy: I know I said I wasn't gonna answer this question, but a couple of things that popped up, while Jasmine was talking. I've sort of seen it where Pacific artists can be pigeonholed into a particular type of making, and it's like, fit this mould.

But I think there are amazing artists, Pacific artists out there who are doing really interesting things, like, sort of contemporary things that it's not necessarily about material culture. It's not necessarily about tradition. It exists in this sort of contemporary cosmopolitan sort of way. I think that pigeonholing can kind of undermine these sort of practices.

George: You have helped to provide a bit of community engagement and facilitation. How did those experiences with your own community shape the work you make?

Jasmine: It shapes a lot of my work, the workshop side of it. I think not even making it. It's just being together with other people and the act of coexisting with other people. So that’s where it kind of stems from, that’s how I’ve approached all my other workshops and collective making collaborations. It's understanding that, both individual and community can go hand in hand.

That is my own personal experience of it. You know, you thrive when you do your practice for yourself, but also giving back to the collective that you come from. So how does that shape it? It shapes a lot of things, my thinking, the way I hold relationships the way I work. Sometimes they might be different to how other people see it, but that's what I know. But it also shapes the way that I'm open to receiving feedback. Jimmy's work and my work are, I think they're pretty similar in terms of concepts and ideas, but material wise, it's pretty far away from each other. So we’re finding that common ground about being Samoan.

And mostly because of our humour, it's worked. Being comfortable to share an idea and be like, okay, cool, that’s not my experience but I see that.

Jimmy: Yeah. I think that the idea of community and collective and stuff is an inherent thing for Pacific people. First, it's the family and then it's the wider family and so on. A core part of my work is talking about experiences that are close to me and to my family. I'd like to think that they're not, they're not unique to me and that some of them are actually shared experiences.

I'm not trying to represent a particular community but making work for maybe afakasi like myself who can relate to it. As Jasmine touched on earlier, that sort of idea of authenticity is something that I have sort of struggled with. It really comes out in my work and, a lot of the works in the show are sort of questioning that idea of authenticity what makes a real, upeti or the rubbing tablet or, real i’e and it raised the question “am I a real Samoan?”

George: Well, I feel like you guys just answered my next two questions to be honest, so I’m gonna move over to the last one. Have there been moments throughout this collaboration that have changed the way that you each see your own work?

Jimmy: Yeah. It's made me realise that I don't necessarily have a craft. And working with someone like Jasmine who has a clear distinct craft in tapa making, I'm sort of like, what is my craft? Maybe I need to get better at carving or something like that. I’ve also started to think maybe the work is just a little bit too heavy and I need to make something that looks pretty too. I don't know.

Jasmine: I think the biggest thing for me is that I make tapa, making tapa is not general knowledge, and I think it's a huge privilege to know and access making tapa, to not just read about it, but practice it. That’s one thing I learnt, I think an example of it was we were doing a test strip, and we were talking about how to print it, using the rubbing board. Jimmy had a different idea, and I think that's because of his screen-printing background. So when I showed him the whole process, it was different to what he thought, which was interesting for me. These are not just things that you just be like “oh, yeah, could you do it this way?”

But other than that, I also realised that I could do whatever I want with tapa, not just stitching. It's been a real fun process, making with Jimmy around. You know, we're talking about authenticity and questioning ourselves of why we're doing this thing even though we know why.

George: This next question you guys have already answered. I'm gonna probably get just a little bit deeper about it. What make tapa or upeti or i’e authentic? What are the challenges of working with such materials?

Jimmy: This is a tricky one to answer because I don't really claim that any of the things are authentic - I'd like to leave that to the person who's looking at it. What is authentic? This idea of cultural authenticity, whether that be within oneself or material culture - what makes this thing real? It is real to me. It’s true to me and my family and collective experiences.

So that notion of what is real is something I kind of like to challenge, within reason. But yeah, I don't want to say it's real because I said so. It’s up to you what you think of it.

Jasmine: The personal connection you make to material culture. So I can’t say this is real. This is what this is. This is what I made. This is what we made, and this is how I'm presenting it for you guys to engage with it and decipher it.

George: But carrying on from that discussion and the notion of traditional vs contemporary, does using a upeti or screen printing change the meaning of the design?

Jimmy: In this case, I think it's interesting because I think the patterns on one hand is like a sort of traditional, the tasina, horizontal lines there, which is a classic motif in Samoan siapo. And similarly with the sort of fala designs there. But I incorporated the paisley pattern, into the rubbing tablet. I think I should probably give some context that the, the idea for this topic was to talk about the things which influenced the development of Pacific identity in Auckland.

I think, you know, talking to my dad, he grew up at a time just after the Dawn Raids had happened, racial tensions were quite high. My dad was a rapper. And so it's kind of unusual, but he saw similarity and familiarity elsewhere, that happened to be The States. You can sort of see the impact of that in our communities today where there's Samoan rappers from Australia, from New Zealand. There are gangs too. And the paisley pattern was an acknowledgement of that. That is uncomfortable, but it's not an uncommon reality for a lot of Pacific people. So on one hand you have got this really traditional object in the upeti, but you've got these sort of things that are feeding into it – like the paisley pattern.

Jasmine: I think that using the upeti and the tools and the beaters it changes a lot of things. Tapa in Samoa is an undecorated tapa, even the action of putting on ink makes it different; it gives a different meaning. Siapo mamalu is freehand, Siapo tasina is using this [upeti] and adding patterns on top of it. Siapo elei is using the rubbing board and then there is Siapo Su’i which I did just make up. This is what I call the practice. So it changes a lot of things. And I think this for this piece specifically, it changed a lot of things for me, because I don't usually work with this process of decorating tapa with ink all the time, or pigment. I've worked with it before, but, traditionally, I don't.

And I think having those patterns Jimmy was talking about, on tapa, it envelopes all these conversations about identity and locating my practice, or our practices in the timeline of Pacific material culture, or Samoan specifically. The actions of adding things tell different stories which I really enjoy, and I am excited for the future of tapa practices.

George: How do you balance tradition and your ideas in your work?

Jimmy: The idea of the traditional thing and not having grown up with it, there was never someone who taught me how to carve or taught me, you know, whatever. I acknowledge tradition – absolutely! I work with it regularly. I see it on a daily basis I like to challenge it a little bit.

Jasmine and I work at Auckland Museum. I had said to my head of department the other day that if my ancestors had a CNC machine, they probably would have used it. And I think that's evident with like going from stone tools to, metal tools, you know?

I think that tradition or the idea of tradition, isn't a fixed thing. I think it can develop. It can, move forward or adapt to the times, and the technology that's available to them. In saying that I think that the thing that I admire about Jasmine's practice is that Jasmine knows how to harvest the, the u’a, knows like when to do it, knows the processes, how to beat it, how to scrape it, knows the knows, the real process of tapa making, but then adds her own things to it. Jasmine does something else to it and tells her own story through it.

And I think that's really important for at least developing the practice. Jasmine and I have spoken about this heaps. I don't want to get too deep into it, but in Samoa there are tapa makers right now who are making tapa - it's an active living practice. I think it should be able to be edited, developed, and adapted.

Jasmine: That was the point I forgot - the technology of time. I think that’s the biggest drive of being able to do different things with tapa, there’s introduced materials, it’s inherent we just try things and make it look fun. You know, there’s lavalava that we’ve added our touch to it. There’s just so many things that’s not just tapa. And acknowledging that there’s tapa makers out there that do the real thing, they do the work. Making tapa doesn’t make me like, a “practitioner”. I'm just contributing to making tapa.

I guess that kind of speaks to the maker part, it’s just something I have the privilege to learn how to do. But these people have lived and breathe this practice, which is really important to acknowledge. If our ancestors had access to technology right now, they would probably be doing the same thing or even better. At the Museum you see all these amazing taonga and measina and “why are we doing that?” We are doing that in different ways, but our ancestors are still better.

George: Thank you so much. Just to go get into the last segment of this artist talk, you guys are totally welcome to ask your own questions if you, feel like, but not yet. We just have one more segment, which is the Instagram question sticker. We only have one, for each artist, Jasmine and Jimmy, which is a lie because I put in quite a few. But, anyway, Jimmy, institution versus self-taught, your thoughts?

Jimmy: I think it depends what you're wanting to do. A master carver doesn't need to go to uni to learn carving you know, they can learn that from a master. I think that's the same for any craft. You don't need to go to uni to learn those crafts. So it depends on what you're trying to do.

For me, I went to Unitec. I did the Bachelor’s Degree and went on to do my Masters and I had a great experience there. My supervisors were great, Leon Tan and Elizabeth, both really awesome. They gave me the space to experiment with these ideas, develop these things that I’m thinking about. I think it really depends on what you're trying to achieve. I'm not saying you can't be an artist if you haven't gone to Elam or one of the things, you absolutely can.

It comes down to what you want to achieve.

George: Last question for Jasmine. How does it feel to be in vogue? What? I'm kidding. For Jasmine, do you believe Siapo practitioners should make their own and why?

Jasmine: I saw this question before, it’s an interesting question. I don't think whatever I believe matters anyway for tapa making. But do I believe that you have to make your own to be a practitioner? Not necessarily. I think because the way that I learnt, I went back home and then I learnt from a family friend that turned out to be a great, great auntie. Anyway, and she was making it. Her daughter was making it. Her granddaughter was helping us making the tapa, helping teach me how to make tapa. And there were men involved as well, harvesting.

So I think it shouldn't be separate. Whatever you contribute to making tapa, it should be yours. And even if that's through gifting, if I was gifted tapa and I wanted to make something on it, I would do that, and I will call it mine because that's my tapa. That doesn't dismiss the actual tapa practice. I also acknowledge it's not just based on making. It's based on knowledge that’s being passed through, and the relationships you hold around it.

Audience Question: Thank you very much. Sorry we came late. My name is Vasemaca Tavola. Thank you for having us in the space that you created -curatorial, leadership - thank you.

I think I just I've been ruminating on this thought about what the subject represents as you just mentioned. It's the relationships, its ancestral wisdom, it's ecological wisdom. It's literally the footprint of our ancestors. So, in that is also its functionality as material culture and how it's used in relationality and how it's used to fortify our bonds.

And so, I'm wondering what your politics are in terms of creating something which is essentially a commodity that is sold in the art market. What are your thoughts around that?

Jasmine: Can I ask a question to your question? Do you mean, like, how it, exists in the art market?

Vasemaca Tavola: Well, I guess, like, what does it take with it? Are you selling that to the buyer? Yeah. Or are they buying essentially a painting?

Jasmine: I haven't had much experience with selling works, or tapa works that are not what I want to sell. So, whenever I am able to sell works, I always put up the works that are that are, like, bits of memories that are important to me, but I'll always have to explain.

This is not just this piece. And I sell it with the assumption that they know what tapa is. Yeah. And that's why I said I haven't sold because I always exchange, I always gift it.

Vasemaca Tavola: How does your dealer feel about that? Why? Do you have a dealer?

Jasmine: Oh, I don't have a dealer.

I think that's a big part of it. I had experience with a dealer, and it's great experience for an artist. It's not for me. Even exhibitions.

This is my first exhibition in a year because I needed to get just kind of get away from the politics or not politics, that's a fancy word, the art world. Trying to be back - why do I actually make tapa? Why what do I want to give and share with tapa? There's a whole lot of emerging artists that are amazing and also look at tapa as an influence.

But what do I want to share with tapa? I hope that it just brings it back, because we use it as a commodity and it used to be a domestic, material. I just want it to be back in our everyday life, no matter if its decoration, or a gift, or something that I use at home to paint on. I think I've mentioned this earlier, family is the most important thing to me.

Audience question: Kia ora, I just wanted to say thank you for acknowledging your manuhiri and unpacking Pacific people in relation to colonisation and also understanding that the people from this mana whenua also have the experience of colonisation. I just wanted to say one thing which is, particularly about Māori art, and particularly contemporary Māori art is that it’s the continuation of a cultural practice and even though we might use different technologies, the mauri is the same, and the transmission of knowledge and the transmission of history, whakapapa, all those things is still inherently in the work. I can definitely see that within your work, Jimmy, I wanted to ask you about collaborating with your dad, because I feel like that has always been a part of your practice.

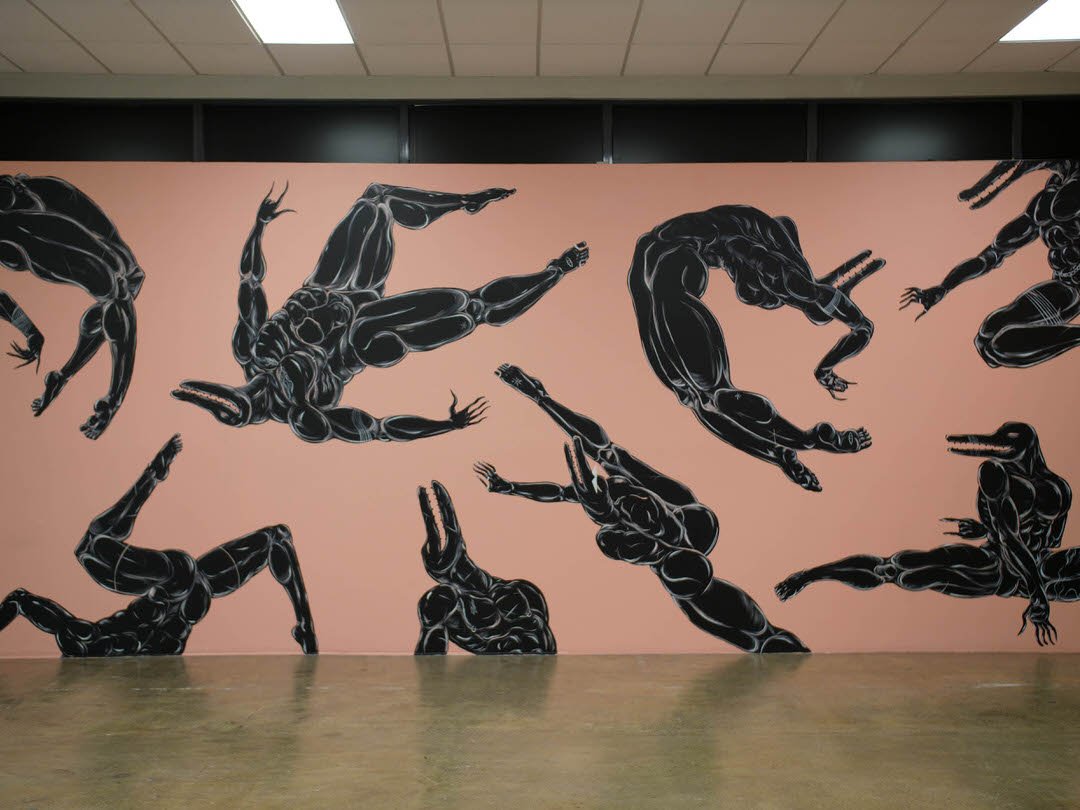

Jimmy: I think I mentioned it earlier, but family is the most important thing to me. I think it's a shared sort of feeling amongst Māori and Pacific communities. And working with my dad has been interesting. I think the works around the corner, the screen prints there - my dad works as a screen printer. He's done so for ten years. I've worked with him for a long time.

The screen prints are important for a couple of reasons. My dad is super hardworking. And he does so for his family.

And, I wouldn't say it's low skilled work, but I was doing some research, last year, and noticed that Pacific people are overrepresented in what the census defines as low skilled work. I use things like the high vis paint that you see around the on the prints around the corner. I love the way that the prints are displayed and kinda like a factory line to sort of just to acknowledge that it isn't a unique experience. This isn’t unique to me.

I'm sort of doing these things, working, making these things, not for clout or anything like that. I want to be able to give back to my family, that sort of stuff. Working with him is great. It means a lot. He's funny to work with though. We have very different processes, mental processes. He's very methodical and I'm very much not.

Jasmine: I do like to add, though, Jimmy's work, is based around labour, and that comes through a lot. Jimmy’s dad is an orderly person, a really tidy person.

I hear things about Jimmy’s Dad and then I met him and I'm like “that’s a hardworking Samoan man.” This is not uncommon for Pacific. And though we are different families, we're used to that. It makes me think about all this low skilled work that's repetitive it is the foundation of how and why we're here, who we are.

I just want to say to Jimmy - your dad's cool.

Audience question: I'd like to just ask you about your choice of the paisley print in there. Because for me, the paisleys are a deeply colonial image.

Jimmy: So really, the reference is to the bandana prints. It's a reference to the gang culture that has been adopted by Pacific communities here. Growing up I went to, Kelston Boys High School and everyone had like a sort of three letter gang that they affiliated themselves with. That wasn’t uncommon. It was everywhere. The same goes with the gang culture now and I think that's down to sort of systemic racism and marginalisation forcing people into joining these things for a sense of community or for a better life or whatever they think it's going to be for. It is sort of topical because the patch ban is happening, and you're sort of incarcerating an already marginalised group of people for seeking this sort of community, seeking a better life or whatever it is. So that's the main reason we included the paisley pattern on that.

Audience response: It's interesting too because it’s associated with paisley in Scotland and with the British textile industry. But they ripped it off from India. You can find it in some Hindi and even in Sanskrit.

Audience response: Even earlier than that, it's Persian. It has been stolen by everyone, so yeah it's very interesting to hear your use of it. So, you're claiming it to tell a story.

Jasmine: I also think it's like our conversations, is a big part of the colonial hangover of these patterns and patches and symbols that we use. You know, these things that we kind of are adapting, working with and having it become an identity.

Past Exhibitions

-

A Seat at the Table

Teuila Fatupaito, Latamai Katoa, Sisi Panikoula, Brett Taefu, and Daedae Tekoronga-Waka.

Dec 5 – Dec 20 2024

-

Solesolevaki

Solesolevaki, initiated by artist-curator Vasemaca Tavola, explores the concept of solesolevaki as a tool to enable connection and intergenerational cultural transmission, across four generations of one family. Featuring works by Lanuola Mereia Aniseko, Ella Carling, Tiana Carling, Mereia Carling, Mereia Sauvukivuki, Helen Tavola, Kaliopate Tavola and Vasemaca Tavola. Exhibition design by Christian Carling.

-

When it Feels Over

Christopher Ulutupu

TAUTAI Pacific Arts Trust, in collaboration with CIRCUIT Artist Moving Image, is pleased to present Leave room for Jesus... (2023) and The Pleasures of Unbelonging (2023) moving image work by Christopher Ulutupu.

-

Grasping the Horizon

Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss

In this exhibition Cora-Allan Lafaiki Twiss’ connection to the black lines of her ancestors are opened wider with a range of new patterns and new hiapo compositions.

-

Good Hair Day

Good Hair Day curated by Luisa Tora explores urban narratives around hair. Featuring artists Bali Buliruarua, Māia Piata Rose Week, Nââwié Tutugoro, Karlin Morrison Raju and Peter Seeto Wing.

-

Titiro ki muri, kia whakatika ā mua | Look to the past to proceed to the future

Coinciding with the Hōteke (winter) holidays, this programme has been organised by Hana Pera Aoake and Tautai Pacific Arts Trust.

-

Queen Fiapoto: switch, code, reverse

Queen Fiapoto: switch, code, reverse is an exercise of agency by 5 young Samoan women. The multidisciplinary project is presented by the sugaz of Malae/Co.

-

The Last Kai

The Last Kai exhibition cleverly uses familiar religious iconography from within Pacific homes to bring up current discussions around women’s representation and the role of Christianity in the modern Pacific household.

-

683 Baby xo

683 Baby xo examines the complexities of being New Zealand-born Niueans, craving that connection to their Niuean heritage while acknowledging their perspective as diaspora youth. Featuring work by Dahlina Taueu, Quentin Tauetau-Tohitau and Kordell Cameron.

-

Taputapu Ātea

Taputapu Ātea is an installation of new paintings and digital works that explore the artificially intelligent future of our culture’s materialisation.

-

Haus of Memories

Haus of Memories is a multidisciplinary residency project led by Studio Kiin that explores and gathers fragments of how we archive and draw upon memory to honour our future past.

-

lean into the pain: archive of a tatau thesis

Award-winning producer and sound artist Anonymouz presents a deeply personal multimedia exhibition that explores his thesis on the Indigenous practice of tatau being an analogue metaphor, philosophy and framework for lived experience.

-

The Water Tastes Different Here

In*ter*is*land Collective, a misfit collection of queer, moana artists and activists based in London, UK and in Aoteraoa New Zealand, present their first exhibition in Aotearoa at Tautai Gallery.

-

Toitū Te Moana

Hawaiki, the ancestral homeland, is the beginning point for Toitū Te Moana, and the place from which the artists’ mātauranga, their knowledge, descends.

-

Oh My Ocean

Curated by Nigel Borrell, this exhibition includes work by Rawiri Brown, Fa’amele Etuale, Ioane Ioane, Elisabeth Kumaran, Sani Muliaumaseali’i, Michel Mulipola, Iata Peautolu, Keva Rands and Chris Van Doren.

-

Moana Waiwai Moana Pāti

Moana Waiwai Moana Pāti celebrates the diversity of Pacific creatives, and includes film, digital image-making, painting, tatau, poetic prose, sonic landscapes and performance.

-

Voyagers: The Niu World

Combining pieces created during Aotearoa’s lockdown and new work, this exhibition aims to tap into the spirit of the great explorers of the Pacific, consulting the stars and charting a course into the wild blue expanse.

-

Saltwater / INTERCONNECTIVITY

Tautai Gallery is transformed to embody the Moana / Solwara worldview

-

Moana Wall

The 70m hoardings were transformed into the MOANA WALL using the existing infrastructure as a canvas that highlights contemporary Pasifika artists and celebrates the diverse community of Karangahape Road.

-

Moana Legacy

Tautai’s first exhibition in its new gallery space, the show was developed from an existing partnership with Blak Dot Gallery, Naarm (Melbourne) featuring Tagata Moana artists working in both Aotearoa and Australia.